Philips Lumify Case Study:

A Patient with Dyspnea

by Dr. Sara Nikravan

In this Lumify case study and summary video, Dr. Sara Nikravan discusses how she used her Philips Lumify handheld ultrasound system to guide the diagnosis and treatment of a patient experiencing shortness of breath. Studies advocating point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for the assessment of unstable patients by non-cardiologists were first published over twenty years ago because of the feasibility, time-effectiveness, and diagnostic accuracy of POCUS when compared to more invasive measures. Over the last twenty years further validation has led to the release of consensus statements from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE), and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP).1

Clinical Case

A 69 year-old male with a known history of hypertension, chronic non-oliguric kidney disease, insulin dependent diabetes, and chronic systolic heart failure with an ejection fraction (EF) of 25% secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy was recovering in the CardioVascular ICU after four vessel coronary artery bypass grafting. His post-operative course had been complicated by acute respiratory failure, acute on chronic non-oliguric renal failure, delirium and pseudomonas pneumonia. The patient’s oxygenation had been improving on antibiotic therapy with aggressive diuresis and ionotropic support, although his BUN and creatinine remained quite elevated. Family had been reluctant to initiate dialysis given his clinical improvement and ability to make urine with diuretic support. The patient was extubated to high-flow oxygen by nasal cannula after successfully passing a spontaneous breathing trial, although, he had failed extubation one week prior secondary to acute dyspnea and hypoxia. Two days later, the patient began to have a fever, worsening shortness of breath with increased oxygen requirements, and inability to wean ionotropic and vasopressor support further. Because of concern for septic shock, the patient was given a total of 500ml of crystalloid overnight. Whole blood lactic acid levels returned at 1.6, serum creatinine increased from 5.8 to 6.11, and the patient’s fever and shortness of breath worsened. Repeat cultures were obtained and antibiotic therapy was broadened further while initiating non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for acute respiratory distress. In the interim, while awaiting laboratory results and chest X-ray imaging, POCUS with a three-point exam (F-TTE, IVC collapsibility, and lung ultrasound) was used for bedside evaluation of the etiology of the patient’s dyspnea. Within minutes, and with the additive information from the combined cardiac, subcostal IVC, and lung ultrasound imaging, the patient was diagnosed with acute on chronic congestive heart failure and flash pulmonary edema as the cause of his respiratory distress and hypoxia.

Stanford University Hospital & Clinics Department of Anesthesiology,A case study by

Sara Nikravan, M.D.

Peri-operative and Pain Medicine Division of Cardiothoracic

Anesthesiology

Division of Critical Care Medicine

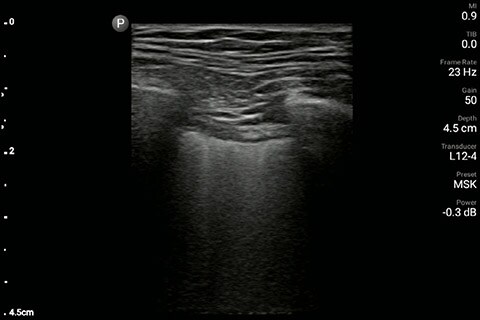

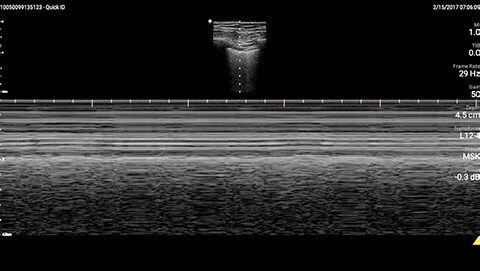

The patient had reduced LV systolic function without new or severe valvular pathology, a dilated, non-collapsing IVC, and diffuse B lines (left greater than right) on lung ultrasound imaging.

Apical 4-chamber

Lung image of the left chest

M-mode demonstrating lung sliding

Parasternal long-axis

Inferior vena cave

Lung image of the right chest

Click here for an abbreviated version of the case study with videos

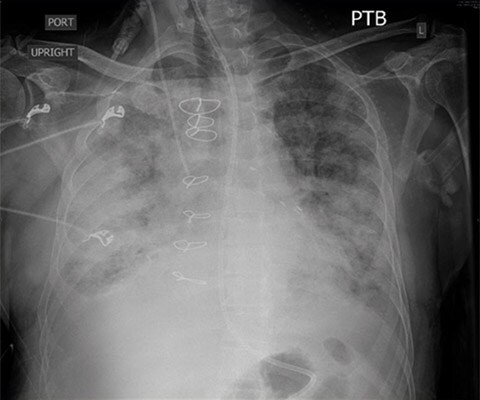

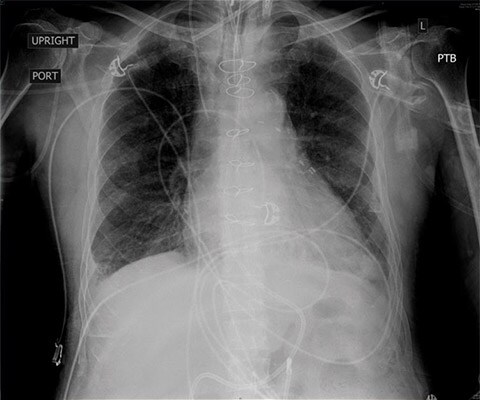

Given his renal failure and anticipated limitations to aggressive diuresis with medical therapy, arrangements were made to emergently intubate the patient, augment ionotropic support, escalate diuresis attempts with diuretics while calling the family to discuss care options including likely need for dialysis. As the patient was being prepped for intubation, X-ray imaging was obtained confirming the diagnosis of pulmonary edema. By then, though, the patient had already been given aggressive diuretic therapy, received escalating ionotropic support, bronchoscopy was set up at the bedside for endobronchial evaluation after the intubation given his fevers, and the family had been notified. POCUS with a small, extremely portable device had allowed for convenient and rapid evaluation, diagnosis, and intervention in a complex patient. A repeat chest X-ray just one hour after intubation showed marked improvement in the patient’s pulmonary edema.Clinical impact

CXR pre-intubation showing diffuse bilateral alveolar and interstitial pulmonary edema.

CXR one-hour status post intubation, after initiation of aggressive diuresis, augmentation of ionotropic support, and positive pressure ventilation.

Discussion

Determining the cause of respiratory distress in the acutely ill can be challenging. POCUS with a three-point exam (F-TTE, IVC collapsibility, and lung ultrasound), as performed above, has been endorsed in this patient population as it can increase diagnostic accuracy in a timely fashion, especially as it pertains to acute decompensated heart failure.4 Furthermore, the use of a small portable device allows for convenience with rapid setup and use while minimizing the uptake of space. This becomes especially important when caring for patients that often have many providers attempting to provide care and initiate interventions at the same time, given the acute nature of their illness and potential for further rapid de-compensation. *Results from case studies are not predictive of results in other cases. Results in other cases may vary. References: